Black History In Liberty

In 1995, Three Gables Preservation conducted a survey of the historic African American buildings in Liberty, with the purpose of determining eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places and receiving assistance with preservation. In order to provide historical context, Deon K. Wolfenbarger compiled a thorough summary of the African American experience in Liberty, an experience that had been largely overlooked in other studies. Wolfenbarger’s research, with the assistance of Brad Finch and Janice Lee, is unparalleled in its scope and provides us with an honest, factual understanding of the hardships African Americans faced since Liberty’s founding. More importantly, the report celebrates the determination and resilience of the African American community as they built and laid down roots in this town. With the pillars of education, worship, and business ingenuity, African Americans in Liberty paved a way for themselves and created a solid foundation of community and service for future generations. Part of grasping the injustice of the segregated and mostly unmarked graves in the burial ground is uncovering the history of who these people were: living, breathing humans, each with a story all their own. In learning the historical context of the African American experience, we can gain insight into their hopes and struggles, dreams and challenges, and come together to honor them in their final resting place. The historical summary of Wolfenbarger’s report can be found in the text below. Click here to view the report in its entirety.

David McClain’s mural on the third floor of the old courthouse depicts selected early 19th and 20th Century African American pioneers, businesses, churches and schools. It is a celebration of the resilience of the first African Americans in Clay County and the contributions they made to the area.

African American Architectural/Historic Resources

Liberty, Missouri

Survey Report, Historical Summary: Pages 11- 28

Prepared by Deon K. Wolfenbarger

Three Gables Preservation

with Brad Finch & Janice Lee

The African American Experience in Missouri

Prior to the Civil War, most African Americans in Missouri lived in what R. Douglas Hurt, author of Agriculture and Slavery in Missouri's Little Dixie, has termed "Little Dixie." New settlers to these counties came primarily from the Southern states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. The Southern culture that these settlers brought with them included commercial agriculture in the form of tobacco, hemp, and hogs, which in turn was dependent upon slavery. Hurt identifies the following seven counties as the heart of antebellum Little Dixie: Clay, Lafayette, Saline, Cooper, Howard, Boone, and Callaway. The slave population of each county in 1850 comprised at least 24 percent of its total population. These counties ranked among the top ten slave counties (by population) in the state, and were leaders in tobacco and hemp production.

Hemp and tobacco crops dictated intensive, back-breaking labor requiring many hands -- work deemed more suitable for slaves by the farm owners. Accordingly, most African Americans living in antebellum Missouri were brought there as slaves for agricultural work. A relatively few African Americans were free. They worked as laborers, particularly on the levees or river boats, and as domestics. Before the Civil War, free African Americans could own property (including slaves), sue and be sued, and testify in court against one another. Otherwise, law and social mores tightly restricted their actions. Beginning in 1835, free African Americans in Missouri were required to have a license. An 1859 measure that just missed being enacted would have required free African Americans in Missouri to either emigrate or become slaves. In 1860 Missouri had 3,572 free African Americans and 114,931 slaves.

The Civil War brought many changes for African Americans in Missouri. Many took advantage of the opportunity to escape slavery by joining the Union Army. Missouri had seven African American regiments. The African American solders' freedom was only comparative, however, since African Americans were treated unequally and were likely to be killed if captured by Confederate forces. A more positive by-product of African American involvement was enhanced self-esteem, as African Americans soldiers had more freedom of action and control over their lives than when they were slaves.

According to military records, 67 Black men are known to have enlisted at the Union Recruitment Station in Liberty, with only a handful returning after the war ended. 25 of them were confirmed deceased in battle or from disease, with several other men disappearing from records altogether. Possible outcomes include captured/killed by the Confederate army, unrecorded death, desertion to freedom, or living elsewhere after their term of service was completed. Enslavers who pledged loyalty to the Union received $300 compensation for the enlistment of the men they enslaved. Click here to read more about the Black men from Liberty who served in the Union army.

The freeing of Missouri's slaves on January 11, 1865, effected even more drastic changes in the lives of African Americans. Increased opportunities were met by almost as many obstacles. The first order of business was attempting to find family members dispersed by the slave trade. These efforts were time-consuming, expensive, and often fruitless. Then, ex-slaves had to begin new lives with little or no resources, and few jobs available to them. Many white Missourians still opposed the idea of emancipation, even if they had to comply with it in practice. Some African Americans responded to the animosity against them by leaving the state. By 1870, the number of African Americans in Missouri had dropped to 6.9 percent of the total population. Most who stayed settled in the counties along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, where they were obliged to find jobs with former masters or other whites. Most worked as farm laborers, with the women often working as domestics. During the 1870s some freedmen earned lower wages than those paid to hired slaves before the war.

Margaret Young and her three children were enslaved in Liberty. In 1864, her two young sons, Dowan and Walter, were taken to Fort Leavenworth during a raid by Jennison’s Jayhawkers. The boys served Union officers, were separated during the war, and never saw each other again. Dowan worked for Sergeant Major James E. Strawn, who pledged to find Dowan employment after the war and help him find his family. On Christmas Day 1897, Margaret and her son were reunited after 36 years apart. Stories of reunion were rare and worth sharing. Click here to read the full story of this mother and son reunion.

From the latter decades of the eighteenth century up to World War I, African American progress was halting. The social and economic turmoil of the late 1800s spurred an increase in lynchings, particularly of African Americans. These heinous acts were especially prevalent in Missouri, where fifty-one of the eighty-one Missourians lynched from 1889 to 1915 were African Americans. Housing for African Americans was hard to find and often substandard. A consequence of poor living conditions, general poverty, and persistent discrimination was the rise of African American businesses, fraternal organizations, and lodges. General opportunities for advancement were so limited, however, that by the start of WorId War I, African Americans were leaving the state in large numbers. Those who stayed tended to move to cities.

Following WorId War I, particularly in the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed renewed popularity nationwide. By 1924, 50,000 to 100,000 Missourians belonged to the Klan. The revival was spurred largely by the influx of European immigrants. Foreigners, Catholics, Jews, and African Americans alike were excoriated for their allegedly unAmerican influence. The relative proximity of St. Joseph, a comparative "hotbed" of Klan activity, probably affected the Clay County area.

The African American Experience in Liberty and Clay County

Slavery was common from the time Clay County was organized in 1822 with Liberty as its county seat. Early settlers came primarily from the Carolinas, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Although slavery was prevalent in the area, there were no large plantations, and large numbers of slaves were not needed. Slave-owners used slaves as field hands, housekeepers, gardeners, and nurses. A visitor to the area in 1820s noted that African American women were employed as maids and cooks because few white women would hire out for these jobs.

During the next three decades, slavery was an essential component of economic prosperity in Liberty and the county. By 1849 the population of Clay County consisted of 6,882 whites, 2,530 slaves, and 14 free African Americans. In Liberty 49 individuals owned 157 slaves in 1850. This constituted an average of nearly three slaves per owner, not counting Col. A. Lightburne, who owned eighteen. The total African American population (freed and slaves) was just over 20% of the city's 827 population in 1850. In 1860 the number of slave-owners in Liberty had grown to 82, and the number of slaves totaled 346. The greatest number of slaves were owned by J.T.V. Thompson with forty, S.R. Shrader with eighteen, and Col. A. Lightburne with twelve. The remaining seventy-nine slave-owners each had an average of 3.5 slaves. In that year slaves comprised 25 to 37 percent of the total state population, and approximately 27% of Liberty's population.

Withers Plantation

Articles in the Liberty Tribune indicated a brisk slave trade, with ads simultaneously offering slaves and livestock for sale. Many ads also called for the return of runaway slaves. Slaves were considered such valuable property, comprising parts of dowers and inheritances, that white men were hanged for stealing slaves or helping them escape.

The annual Clay County slave auctions held on the courthouse steps were important to the area's economy before the Civil War. The first auction was held in approximately 1835, after the first permanent courthouse was completed. An observer of an 1849 auction later recalled two classes of slaves: "good, tractable, obedient Negro servants," who comprised the majority, and "the bad, incorrigible type slave who had run away from or attacked his master, or who had become dangerous to society” (5). In 1854 slaves sold for $1,200 to $1,400 each. At one of the last auctions, held in January 1859, $20,000 worth of slaves were sold. By 1861, when Union troops occupied the county, slave auctions had ceased.

Bill of Sale: “Liberty Clay Co MO May 5, 1851. For and in consideration of the sum of six hundred dollars to me in hand paid I have this day bargained sold and delivered unto John A. Beauchamp my negro boy Isaiah a slave for life and sound & healthy in body & mind & free from the claims of any other persons and is about thirteen years old.”

Click here to view more primary historical documents like the one pictured.

During the 1850s, the pro-slavery town's population grew to about six hundred people. Slave trade was heavy in this decade. The potential free-state status of nearby Kansas created much unrest, however. Many Liberty slave-owners worried that the proximity of a free state would increase the opportunities for slaves to escape. Previously, the nearest free state had been Iowa, which was nearly one hundred miles away. These fears occasionally materialized. In 1859 three abolitionists aided the escape of fourteen slaves from Clay County and the surrounding area. A recovery group of about ten men, including some of the most prominent Liberty citizens, tracked the group into Kansas, and captured the slaves near Lawrence. The slaves were returned to Liberty and three of the "conductors" of the Underground Railroad were jailed. Such incidents prompted many area citizens to assist pro-slavery forces in the Kansas Territory. The pro-slavery activity in Liberty exacerbated border guerilla warfare waged in the area.

Advertisement for the sale of the enslaved: Rose (45) , Bill (33), Burrell (21), Martha (15), May Jane (15) - September 2, 1851

Treatment of slaves in Liberty and Clay County was typical for the period and for the Little Dixie area. Lynchings were common, even if guilt was unproven. The last lynching in Clay County occurred in Excelsior Springs in 1925. Fear of lynchings were only one concern for slaves. Before the Civil War, no slave in Clay County was allowed to be out at night without permission from his master, owner, or other "responsible white person." In 1824 the county court established neighborhood patrols that watched roads, camp-meeting grounds, river landings, and other places African Americans were likely to congregate. Patrol members whipped slaves found outside without a permit after nine o'clock. Liberty had its own patrol by 1827.

As in other pro-South states, life was arduous for slaves (6). Labor was hard, hours long, and material possessions -- and comforts -- almost non-existent. Christmas week, a holiday allowed most slaves, provided one of the few bright spots. The only required duties were feeding stock, keeping up fires, and cooking. The slaves held dances, parties, and games, and feasted on opossum and raccoon suppers. It was the custom for area whites to stroll down to observe the festivities.

Relatively few African Americans obtained freedom before the Civil War. In 1829 the first deeds of emancipation were filed in Clay County, when three slaves were freed by their masters. Court records show additional instances of emancipation before the war, but these were exceptions. In 1854, for example, five freed African Americans took out licenses that stated they agreed to live peaceably in the county, and posted bond to swear that they would not disturb the peace (7).

Beginning in the 1860s the African American population in Liberty steadily declined. It totaled 14.1 percent in 1931 and less than 3 percent in 1970. Little has been written about the lives of post-Civil War African Americans in Liberty, but research performed for this survey indicates that their experiences were similar to those of African Americans in other small, previously pro-Southern towns in Missouri.

African American Housing in Liberty

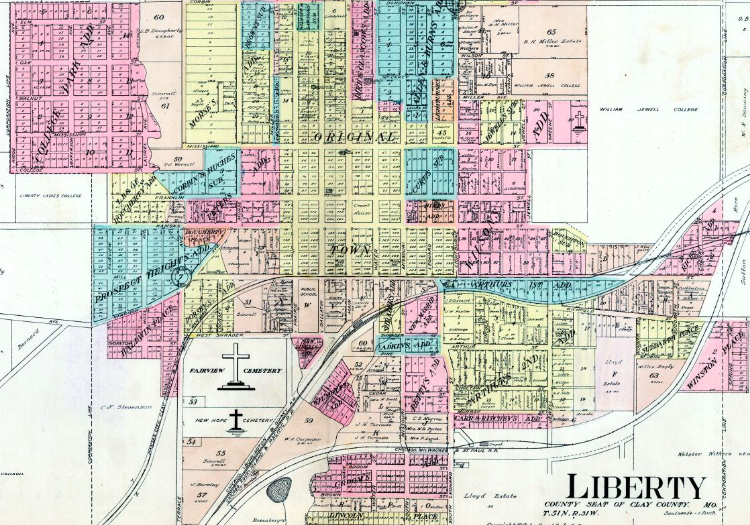

Map of Liberty, 1914

Historically, the African American population in Liberty has been concentrated in two areas. The first area is bounded by Francis Street on the north, N. Main Street on the east, Mississippi Street on the south, and N. Morse Street on the west. It appears that they were set aside for African Americans from the beginning, although documentation has not been found to verify this assumption. The section west of N. Grover was called "Happy Hollow" (it is currently Ruth Moore Park). A second major section is bounded by Shrader, Pine, and Ford Streets on the north, Jewell and Leonard Streets on the east, Murray Road on the south, and the Burlington Railroad on the west (8). This area near W. Shrader is popularly called "The Addition," or New Liberia (the name of the plat). The basic geographic distribution defined by these two areas has remained fairly constant through the present and is illustrated by a 1930s map showing distribution of school-age by race.

As was typical in geographically segregated towns (and most towns were) Liberty residents wanted to maintain the separation of living areas. The official position of white residents in the 1930s, for example, seemed to be that African Americans were a "useful element" whose welfare should be safeguarded, but that separation of housing areas "be controlled by mutual agreement between the races” (9). The proposed method of enforcing segregation was to continue confining African Americans to the two main districts in which they already lived, since there existed "ample area within these districts."

Conditions in these district were, of course, not equal to those in the white portions of town. Houses in the African American sections tended to be smaller, and, given the greater poverty of African Americans, in poorer condition. Electricity, water, and telephone service were installed at later dates than in white homes. Because many of the houses were not supplied with water, it had to be drawn from springs, such as the ones near the present Franklin Elementary School at Mill and Gallatin Streets, and near Pine and Missouri Streets.

Housing standards were particularly low during the Depression. A 1938 newspaper article admitted that "there is not a house that [African Americans] can buy, or rent that is fit to live in, and in a number of cases there are several families living together in very crowded quarters" (10). The housing shortage was exacerbated because many white families were on relief and, unable to afford houses in the white portion of town, bought homes in African American neighborhoods, displacing African Americans from the only neighborhoods open to them.

Even after segregation was declared unconstitutional, African Americans did not move out of the two traditionally African American sections in great numbers. Some, particularly those who had lived in the area for many years, stayed because they were older and had neither the desire or financial resources to move. Many younger African Americans who could have afforded housing in previously white areas moved out of Liberty because of the lack of job opportunities.

Brooks Landing, south of S. Main Street, was important as the first low-income housing area in Liberty, but because of the relatively few houses constructed (fourteen in 1989) it has not had a significant impact on the housing situation. The current rise in housing prices has meant that even fewer African Americans can move into previously white areas.

Some major physical changes have occurred in the two African American sections. In 1939, houses were moved from S. Prairie Street, between Mill and Shrader Streets, to make room for the construction of the Franklin Elementary School. The area called Happy Hollow was transformed into Ruth Moore Park in the 1970s. The construction of Brooks Landing subdivision entailed the removal of existing houses in an area which had become less populated and somewhat neglected. Fourteen new houses, estimated at $43,000 each, were constructed in 1989. Newspapers also tell of several attempts to rezone traditionally African American areas from residential to commercial. The African American community strongly, and successfully, protested the proposed re-zonings. These would have resulted in, for example, the construction of a tin building near the Baptist church, and a car repair garage in the northwest part of the city.

African American Institutions in Liberty

African American institutions, whether social, religious, or commercial, provided the social, economic, and cultural advantages denied African Americans by white society. Churches and lodges contributed greatly to social life by holding fairs, picnics, suppers, and dances. They were also important as ties to other communities -- travelers could stay at homes of members of sister lodges or of church members, often the only lodging available to them. Before the end of official segregation, African Americans operated businesses out of their homes, by necessity. They were not allowed in white establishments, and were not allowed to rent, even if they could afford to, business quarters in town. Segregation, although it achieved nothing else positive, did foster a sense of community for a group that was excluded from full participation in white society.

Education

Between 1847-65, educating African Americans was illegal in Missouri, primarily because an educated slave was considered more likely to rebel. Funds were raised by private subscription for African American children in Missouri after the war, but public schooling would soon replace private instruction for both white and African American children. The first major provision for public education was made in 1865, when the state constitution required public school education for all school-age children (those between the ages of five and twenty-one). City, village, and township boards had to supply schoolhouses for African American children if their number within the area of jurisdiction exceeded twenty. This number was reduced to fifteen in 1868. Schools in theory were to be equal to those for white children but in practice were much inferior.

The next two decades brought more provisions for African American education, but this legislation simultaneously reinforced segregation. By 1870 the Missouri Superintendent of Education could boast that the state provided a greater proportion of schools for African American children than the other former slave states. The number of such schools did increase from 34 in 1868 to 212 by 1871. At the same time however, only 4,358 out of 37,173 African American school-age children were attending school by 1872. Legislation in 1875 stipulated that African American schools should be separate from white schools, and the 1879 legislature made it the duty of the state superintendent of public instruction to establish schools whenever the board of education of towns or cities neglected or refused to. Legislation in 1889 made it unlawful for the two races to attend the same schools. These two pieces of legislation actually reduced educational opportunities for African Americans in rural areas: in small communities African Americans and whites had previously been educated together because of the economic impossibility of providing separate schoolhouses.

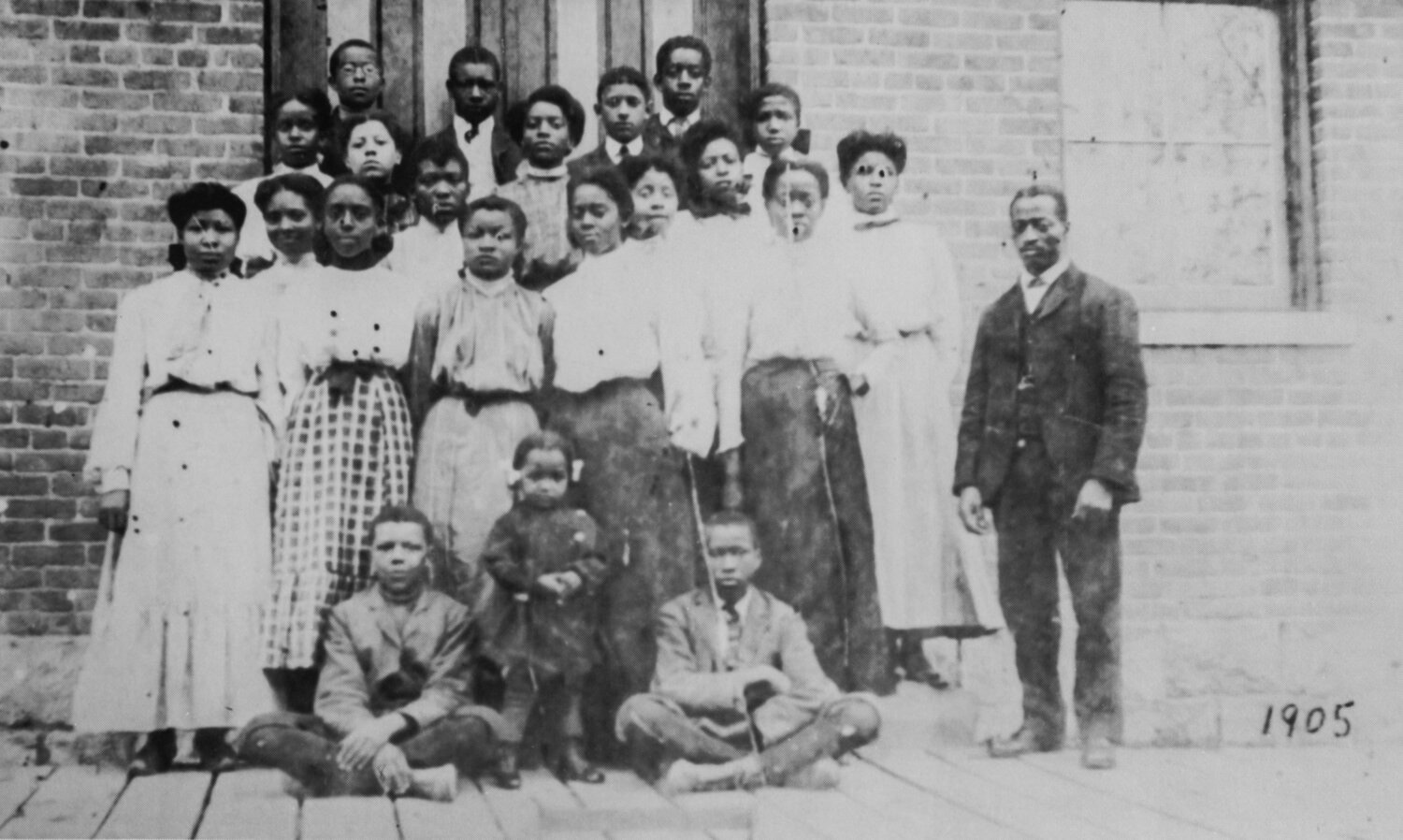

Garrison School, about 1880

None of the legislation produced from the 1860s through the 1880s was able to insure that African Americans received equal education, or any education at all in some cases. Most Missourians' feelings about emancipation in general and African American education in particular were ambivalent at best. Given overall resistance and the relative paucity of educational funds, African American education continually suffered. Each piece of legislation was enacted to close loopholes in preceding legislation, but none were fool-proof: enterprising school boards and local officials found many ways to get around Missouri school laws. In many areas, officials fudged census figures and neglected to hire teachers, select school sites, or provide funds for African American education. Such provisions for African American education that did exist were almost always inferior to those provided for white children. Less money was expended per pupil in African American schools, the buildings were smaller and in substandard condition, and the school terms were shorter. Average attendance was also lower than in white schools.

Education for African Americans improved only slowly in the twentieth century. As of 1911, the state still made few provisions for the education of African American children. There were only eight African American high schools in Missouri by that date, although this number did increase to fifteen in 1915. One historian has noted that in the early 1900s, African American elementary schools outside of cities were "disgraceful." Into the late 1920s, schools for African American (with some exceptions within St. Louis and Kansas City) remained inadequate, As late as 1928 at least four thousand African American children lacked access to schools. School districts outside of metropolitan areas claimed that they had barely enough funds to maintain schools for white children, and that since few African American residents paid school taxes, school boards could not be expected to do much for African American children. Some districts argued that there were too few African American children in their districts to justify building and maintain schools for them, and that there were no schools in the county to which they could be sent. Salaries were lower, sometimes nearly by half, for African American teachers, especially female teachers.

Early schools for African Americans, both in Missouri and across the country, were held in churches, homes, or other "make-shift" facilities. When schoolhouses were built, they were usually of the traditional one-room design, were constructed of frame rather than brick, and had few amenities. By 1900 more substantial schools were being built. A number of African American schools in Missouri were built through Works Progress Administration grants. By 1939 Missouri had approximately 260 elementary and high schools for African Americans.

African American education in Liberty followed the general pattern within the state, with public facilities not provided until the late 1800s. The first school for African American children is commonly believed to have been a subscription school that was established at the end of the Civil War. Mrs. Laura Armstrong taught the school in a room of her home, which was located on W. Mill Street, between Gallatin and Prairie Streets. Students paid $1 a month, and attendance was said to have grown rapidly (11). Lucretia Robinson is thought to have taught the second African American [and Native American] school in Liberty at her residence on 446 N. Water Street. The third school met in the Old Rock Church, located on a hill near where Garrison School is now located.

The original Garrison School, a three-room brick structure, was built in 1880 on the present site of Garrison School, at 502 N. Water Street. It was a grand facility compared to the usual frame, one-room schoolhouses provided for African Americans who lived outside of the larger Missouri cities. Its location was central to the greater portion of the African American population. The school was named for William Lloyd Garrison, the noted journalist and slavery opponent. It offered eight elementary grades and two years of high school. The first graduating class was in 1891. By 1910 the school enrolled 117 students. After this building burned in approximately 1911, the school met in the nearby Masonic Hall until the current building was constructed shortly thereafter.

Garrison School, about 1930

For the first half of the twentieth century, African American and white education remained unequal. School district figures from 1922 provide a typical example. In that year, Liberty enrolled 117 African American students and 905 white students. The school district employed twenty-nine white teachers and five African Americans. The most highly paid were white male high school teachers at $1,039.50 per year, followed by white female high school teachers at $926.10 per year. The most poorly paid were African American female elementary school teachers, at $607.50 a year, followed by African American female high school teachers at $630 a year. This disparity was in no way unusual, for differing pay scales based on sex or color were commonly accepted practices during this period. The school board might have justified (though it is doubtful that justification would have been called for) the racial pay disparity because of the fewer hours of college education completed by the African American teachers. Four of the African American teachers had completed 60-89 college hours, and one had completed at least 120 hours. In contrast, five of the white teachers had completed 90-119 college hours, and twenty-four white teachers had completed 120 or more college hours. The one African American teacher with 120 or more college hours apparently did not earn more than his less-educated African American colleagues. The lower number of college hours completed by African Americans was not unexpected, since opportunities for higher education were so limited.

Clara Bell Colley with students at the Garrison School in the 1950s

The 1930s were a busy period for Garrison School. Although the school remained small, having only six graduates in 1935, in that year the high school track team took third place in the state. It was the only high school with less than one hundred students that was listed in the top ten for track. Also in that year, a newly organized PTA managed to procure a first aid medicine cabinet from the Board of Education, although the parents had to stock the cabinet themselves. By 1939 the building had become worn and was somewhat outgrown, as attendance had grown to approximately 142 in 1938. Remodeling and an east addition were completed in 1940, financed jointly by a Public Works Administration grant and bond funds. Two lots were also purchased in order to accommodate the addition of a combined auditorium/gymnasium and more classrooms. During this and the next decade, the number of graduates per year averaged about seven.

In 1953, under pressure from school patrons, the Board of Education voted to close the high school section of Garrison School and transport students to Lincoln High School in Kansas City. Parents requested that the students be transferred so that they could take advantage of the more extensive course of study and the additional activities offered by a large high school. After desegregation in 1954, the building was remodeled to serve as a Kindergarten. It was furnished with a gas furnace, new drinking fountains, new flooring and lights, and a hard-top playground. A hot lunch program was offered.

Football Town Team, organized by Arthur Willis in 1915

Although arguably large enough to house all of Liberty's school-age African Americans, Garrison School did not offer facilities equal to those enjoyed by whites. According to former students, the building was not well-maintained and schoolbooks were worn, outdated cast-offs from the white schools. Individual teachers sometimes taught more than one grade. Newspaper articles do indicate that the school had a number of outstanding athletic teams through the years.

Garrison School is significant for being the site of the only public education facility for Liberty African Americans from the early 1900s until the 1950s, with the current building serving this function for nearly half a century.

Churches

Prior to the Civil War, whites and African Americans in this country worshiped in the same churches. During the war it was considered particularly prudent to keep African Americans as members of the white churches. Most slaves never felt completely at home in the white man's church, however. The slave recognized that "the master could be at ease in any part of his church edifice. It was all his and he moved about through its aisles as a free man, but the slave was limited in his privileges, and was counted as a good man only as he kept within the limits assigned him" (12).

Beginning in the 1800s, African Americans frequently joined the Baptist church. The freedom and democracy of the Baptist Church enabled African Americans to participate in church affairs earlier than they were allowed to in other denominations. The earliest Baptist churches also allowed whites and African American to worship together within certain limits, although separate treatment gradually became more common. African American were given different hours for worship, for example, or were physically separated from the white congregation. The Methodist Church was the other popular choice for African Americans, because of its egalitarian gospel. As with the Baptist Church, however, equality did not fully extend to African Americans. African Americans might be given Communion separately, and only after whites had received it. After the Civil War, during the early African American independent church movement, African Americans still gravitated toward the Baptist and Methodist churches. African Americans preferred these denominations because of the more emotional form of worship, the absence of formal ritual, and the greater leadership opportunities offered to ministers.

Early African American churches in Liberty met in varying locations. Before 1874 the Baptists and Methodists worshiped together in the courthouse, then a barn on Missouri Street. During this period the school board purchased property on the site of what is now Garrison School for use as an African American school. (The property had previously belonged to the Primitive Baptists.) (13) The "Old Rock School" served as a school during the week and a meeting place for congregations on Sundays. According to one account, the Baptists and Methodists held their services on alternating Sundays.

The First Baptist Mt. Zion Church, about 1890

The First Baptist Mt. Zion Church was the first African American church to be established in Liberty (14). Rev. William Brown organized the church in 1843 when he was in his late teens. After worshiping in the locations described above, the Baptist congregation purchased the present lot on N. Gallatin and constructed a church in approximately 1874. An early member noted that some of the early members "never learned to read a chapter or even a verse of the Bible, but could quote very correctly many passages of Scripture” (15). A church history states that the parsonage was built in the 1890s. The first church building was destroyed by fire and the present building constructed in 1915. Several additions have been made to the church. The most recent is the educational wing and baptistry, added in 1986. The church offered a variety of activities for its members. It had at least six choirs at one time, and other church organizations, which included the Mission Society, the Pride of Zion Club, and the Willa Herring Matrons.

St. Luke’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, about 1938

The St. Luke A.M.E. congregation was organized by Rev. Jesse Mills in 1875, and the church building was constructed in 1876 at 443 N. Main. Previous worship sites included the courthouse, and, when that was no longer available, a horse barn at 102 E. Kansas, and then the Old Rock School. The first services in the new church were held September 28,1876. In 1917 Rev. William Alexander remodeled the church building after a fire. The church partially burned in 1934. By 1938 it had been restored by the Civilian Conservation Corps, and a new basement added. In the early 1940s Rey. A.G. Thurman drew up the plans for the present church and helped the congregation quarry the rock and construct the building by hand. Stone was quarried from the farm of Tom Greene, in north Liberty. He told the church they could have the stone if they would quarry it. The stone was hauled in trucks and then wheelbarrows to the church site, where the church women mixed mortar. Rev. Thurman did much of the mill work himself. It is said that the church was purposely made large to serve as a meeting place for the African American community. The leaded glass windows were added at this time. The new building was dedicated in 1942. In 1978 the structure was awarded Clay County Landmark status. The steeple was replaced in 1985 after it was hit by lightning.

The other significant African American church in Liberty was the Sanctified Church/Church of God in Christ/Humphrey Temple, at 213 W. Shrader Street, established at an unknown date. The church was referred to as the Humphrey Temple after Rolla Humphrey, who helped to build and maintain the structure. It is also colloquially referred to as the "Holy Roller" church.

Social Organizations

African American lodges date back to the 1700s. As the free African American population grew, a variety of African American societies formed throughout the country. The groups were bound by common interests that included literature, temperance, and the promotion of "brotherly love." Masonic organizations were the most important of these societies. In 1775 Prince Hall, the father of African American Masonry, first sought membership in a white Masonic Lodge in Boston. Turned down because of his color, he next approached a military lodge of an Irish regiment that was attached to the British army in Boston. He and fourteen other African Americans were initiated into the lodge. A year later African Lodge No.1, the first of its kind, was formed. Today's African American lodges are descendants of this one. Until 1970, white Masons refused to recognize the African American lodges as Iegitimate.

In northern Missouri, enough African American Masonic chapters existed by 1869 for a conclave to be held. The (African American) Liberty Lodge #37 of the A.F. & A.M. was issued a charter in 1877. The first brick Masonic Lodge structure, built in the late 1800s, was once located on N. Main Street, near the Garrison School. This hall was torn down in the 1930s. In the 1980s the lodge met twice a month in a small hall on Grover Street. The lodge had about thirty members at that time. The lodge [then met] at a former residence at 721 N. Main, next to the site of the former lodge. The lodge also sponsored a women's auxiliary organization, the Eastern Star.

Businesses

African American-owned businesses were numerous during the years that African Americans were not allowed to patronize white establishments.

Almost all operated out of residences. In Liberty, the following enterprises have been recorded: (16)

A restaurant and later an undertaker's establishment in the house preceding the residence now at 404 N. Main Street

The Wiggle Inn nightclub at S. Main and Pine Streets

Cornelius Bird's well-known greenhouse at 442 N. Grover Street, patronized by both African Americans and whites

The Singleton Funeral Home was in operation until about 1938

A grocery store at the corner of the alley at 434 Gallatin Street

A restaurant operated by Henry and Maggie Pearley at 215 W. Shrader. The restaurant was famous for its ice cream, which was also bought by white residents. The restaurant closed in the 1950s when Mr. Pearley died. The lot adjacent to and behind the restaurant featured a public croquet and tennis court in the 1930s-40s. Nationally famous African American tennis players played matches on this court. The lot was also used for African American community events, such as fish fries and carnivals during this period. The residence behind the restaurant contained an addition for Dr. Seymour Pearley's dentist office, who may have been the only African American dentist in Liberty during the 1930s-40s. Dr. Pearley practiced primarily in Independence, MO.

Maggie Collier's beauty parlor

Grandpa Bealy McShear's Pool Hall

Rollie Allen's Barber Shop - 420 N. Main. The barbershop was in the north bedroom of the house. A recent neighbor recalls as a small boy, he sat on the front porch all day talking with the patrons. He said he would get paid a quarter to let people get their haircut before him. He would just sit there all day collecting quarters!

J.P. Jones' Auto Repair Shop

Luther Douglas' Painting Service

Howard Murray's Refrigeration Service

Sam Houston's Custodial Service

Burt McGinnis' Disposal and Second Hand Shop

James Alexander's Horse, Carriage, & Buggy Rental

Elijah Slaughter's Taxi Service

Liberty Friends of Distinction: Vassie Willis, Sue Tag Irvin, Goldie Prince, Ella Mae Hinton, Francis Pearley McGill, Flora Hopes, Ruth Pearley Stevenston, Delcia Slaughter

Significant Community Members

The following (listed alphabetically) were prominent members of the African American community, and were well-known enough in the entire community to receive notice in the local newspapers.

Cornelius Bird (?-1967) owned a well-known greenhouse at 442 N. Grover. His talents and personality transcended the ordinary. One customer noted that "Cornelius lifted plants like babies, not as a new frightened mother might, but with the sure, confident touch of tender love. Mr. Bird gardened because he loved to grow things.... The love was apparent everywhere in his greenhouse. It was a riot of color and an aroma of rich dirt inspired by a man obviously praising God that he had such a gift" (17). A newspaper editorial writer said that although Bird was neither wealthy nor influential, "he will be mourned and missed as few other men in Liberty would." To many Liberty residents he was evidently "a trusted counselor, an initiate in the mysteries of what happens to a seed buried in most earth warmed by the sun. They sought his advice and he gave it freely” (18).

Otis Bird cooked for Liberty Ladies College, William Jewell College (for more than forty-two years), and the Odd Fellows. He was active in Liberty Lodge #37 for more than sixty years, as well as in the Baptist Church.

Katie Brooks came to Liberty in 1903, and traveled worldwide as an ambassador for the Kansas City Passport Club. In the 1980s she was instrumental in developing the first low-income housing development in Liberty. Brooks Landing is located just south of her former residence at 220 S. Main Street. The area, which had once been thriving, had become nearly deserted and, except for the Brooks home, had fallen into disrepair. Mrs. Brooks was nearly ninety when she originated and helped coordinate the project.

''Professor'' James A. Gay (1882-1985), his wife Ethel, and their three children lived on Gallatin Street. He was a graduate of Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri, and moved to Liberty in 1910. He taught at the Old Rock School, located near the current Garrison School, until it burned in approximately 1911. Gay served as the principal of Garrison School for twenty-two years and has been credited for suggesting that the school be named for the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. He tutored William Jewell college students in Latin and Greek and taught night school to local African Americans on his own time. Gay also served as Educational Advisor for the Civilian Conservation Corps, which was stationed at William Jewell College from 1933-42. Gay was one of very few African-Americans to hold an administrative position in this organization.

Sam Houston was First District city councilman from 1975 to 1993 and [wa]s the only African American to have served on the city council. As a city councilman, he was instrumental in bringing about needed changes in the African American community. He [wa]s also active in the First Baptist Church. Houston [wa]s the retired owner of Sam Houston's Custodial Service and a descendent of the Houstons that settled in Clay County in 1844. His wife Mary worked as a legal secretary before retiring.

Rolla "Rollie" Humphrey was born to former slaves around Salisbury, MO in 1875. He came to Liberty from Huntsville, MO, as a young man, bringing his wife and three children. He worked for the railroad, then for the city as a street sweeper, for about thirty-five years. By the 1970s he had outlived four wives. He helped build and then managed the church across the railroad tracks from his house: the Church of God in Christ, 213 Shrader Street, referred to as the Humphrey Temple. In 1975 the mayor of Liberty proclaimed July 4, Humphrey's one-hundredth birthday, as "Rolla Humphrey Day." An open house was held at the church he had helped build.

Hazel Monroe lived in Liberty since 1938. In 1994 she was awarded a Martin Luther King, Jr. Service Award for her devotion to children and to community service. In 1968 she opened Liberty's first owned day care center in her home. Her love for children went beyond the day care center: she also looked out for neighborhood children, helping them get along and teaching them values. After moving to a retirement village she continue[d] to befriend local children. She also g[a]ve bread, clothes, and Bible stores to those in the neighborhood, using items donated through a program in the Second Baptist Church, where she [wa]s a member.

Lawrence "China" Slaughter was born in the first two-story house to be owned by a black family in Liberty, on N. Grover Street. His parents, Anna and Isaac Slaughter, were early residents of Liberty. Anna was chief dietician at the former Major Hotel in Liberty. Slaughter was the Buildings and Grounds Supervisor for the Liberty school district for forty-eight years, and was well-known for directing traffic near Franklin Elementary School for more than thirty years. He organized the first African American Boy Scout troop in Liberty in 1936. Slaughter taught Industrial Education for the state of Missouri for twenty-eight years. He was commissioned by Liberty Police Department in 1942 and served on the city's Human Relations Committee.

James V. Thomas, a paper handler for the Kansas City Star, became the first African-American to serve on the Clay County grand jury and on the Liberty School Board in 1971.

Sources:

5 William E. Dye, "Slaves Sold on Courthouse Steps," Kansas City Times, 16 March 1972.

6 See Lorenzo 1. Greene, et. ai, Missouri's Black Heritage, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1993, for more on slave life in Missouri.

7 Clay County did show some generosity to African Americans after the Civil War. Court records show that the county frequently aided former slaves, especially elderly ones. In 1866, for example, Joseph H. Rickards was paid $20 for supplying necessities to the elderly and infirm former slaves that had belonged to a now-deceased master.

8 The African-American neighborhoods fell into the following platted subdivisions: outlots in the Original Town ofLiberty, platted about 1823; Corbin Place. was platted in 1888; Arnold's Addition. was platted in 1886; New Liberia. platted in 1888; Petty's Addition, was platte4 in 1889; Adkin's Addition, platted in 1881; Willmott's Addition, platted in 1899; Michael Arthur's Second Addition, platted in 1870; Suddarth Place, platted in 1890; Morse's Addition. was platted in 1884; Peter's Addition. platted prior to 1877; M.B. Brown's Subdivision, platted in 1887; and Bird & Glasgow Addition, platted prior to 1877. In 1930, the two sections were defined as follows: the most populous section was bounded by Corbin Street on the north, Water Street on the east, Mississippi on the south, and Morse Avenue on the west. The second area was bounded by Pine Street on the north, railroad tracks on the south and west, and a creek on the east.

9 Hare & Hare, "A City Plan for Liberty, Missouri: Report of the City Planning Commission, 1930-34," 6. Hare & Hare not only recognized the existing segregation but perpetuated the practice in planning by preserving these geographic divisions.

10 "The Liberty Negro is Title of Church Paper," Liberty Tribune, 26 February 1938.

11 One unsubstantiated written account, which is not corroborated elsewhere, states that in 1867 an African American man taught the first African American school in Liberty. He was also said to be the first African American commissioned by Governor Thomas Fletcher to establish free schools for African American children. Black History Files, Clay County Historical Society Archives, Liberty, Missouri.

12 Walter H. Brooks, "The Evolution of the Negro Baptist Church," Journal of Negro History 7 (January 1922): 41.

13 The Primitive Baptist congregation was in existence as late as 1898. In that year they held a two-day meeting at Mt. Zion, probably in conjunction with that church. The event drew a Sunday crowd of 1,500 people.

14 The Mt. Zion Baptist Church is referred to locally as the oldest church in Liberty--white or black congregations. Other congregations were founded earlier; however, the scope of this study did not confirm whether these other congregations are still in existence. The Mt. Zion Baptist Church is the First Baptist Church of Liberty, however, of any ethnic group.

15 "History of First Baptist Mt. Zion Church, Liberty, Missouri," Black History files, Clay County Historical Society Archives, LibertyI Missouri.

16 Addresses and dates are available in only some cases. Attempts were made to trace the addresses and years of operation of African American businesses, but this was not always possible. No city directories are available until the 1960s. Businesses were generally not listed in the telephone directories because they operated out of the owners' homes, and a number of African Americans in Liberty did not have telephone service until as late as the 1950s. The businesses listed here were compiled partly by oral interviews by William Jewell professor Cecelia Robinson and were included in a Juneteenth Celebration booklet.

17 Norma Stever, Liberty Tribune, 2 October 1967.

18 "Opinion," Liberty Tribune, 2 October 1967.